Online Research of Potential Jurors: A Survey of Resources and Ethical Boundaries

Posted by Wetherington Law Firm | Articles

- Articles

- Artificial Intelligence

- Car Accidents

- Class Action Lawsuit

- Comparative Negligence

- Crime Victim

- Defective Vehicles

- Disability

- Kratom Death and Injury

- Legal Marketing

- Motor Vehicle Accidents

- News/Media

- Other

- Pedestrian Accidents

- Personal Injury

- Results

- Sexual Assault

- Truck Accidents

- Uber

- Wrongful Death

Categories

Practice Tips From Matt Wetherington on Juror Research for Trials in Georgia

Note: This article was originally published in 2013. Since then, a lot has changed. But this article is still helpful as a basic primer on online research of jurors. And the ethics rules have NOT changed as of 2021.

Online research of potential jurors can be a powerful tool for screening jurors and ensuring that your client receives a fair trial. Historically, juror research has been reserved for wealthy parties, powerful prosecutors, and “high stakes” litigation. The rise of the Internet and social media has greatly leveled the playing field as any attorney with an Internet connection can now perform comprehensive research on potential jurors.

Over the last decade, social media websites have grown at an astonishing pace. As of December 2012, 67% of online adults use at least one social networking website.[2]

Users of social media websites maintain data-rich “profiles” where the vast majority of information posted is self-published and highly reliable. Many social media accounts offer a unique view into the personal and social life of the user. These accounts consist of personal views and opinions on a variety of topics ranging from politics, religion, family values, and the latest episode of Breaking Bad. The richness of data, coupled with the ease that it is found, make these accounts very useful for supplementing the voir dire process and then tailoring presentations to seated jurors.

The usefulness of online research of jurors has been addressed by courts and bar associations throughout the United States, as many have begun issuing opinions that embrace online research of jurors. In 2012, the New York City Bar Association issued a formal opinion stating that failure to perform online research of prospective jurors may be tantamount to malpractice.[3] “[S]tandards of competence and diligence may require doing everything reasonably possible to learn about the jurors who will sit in judgment on a case.”[4] Courts in Missouri and Florida have offered similar opinions.[5] Wisconsin courts have even embraced the notion that online research can be a strong defense to a Batson Challenge.[6]

The key function of online juror research is to eliminate biased jurors during the voir dire process. However, online juror research is not a substitute for conducting a thorough voir dire, and professional juror consultants have advised caution in relying on social media research too heavily. Renowned trial consultant Charli Morris frames the issue stating: “I have, in a handful of cases, found information online that proved critical to our decision during jury selection. But I would trade all the online research in the world for effective attorney-conducted voir dire and cause challenges granted where appropriate.”

In addition to not replacing voir dire, online research is also ripe for wasted time if the research is not conducted in a manner that avoids false-positive results and/or too much energy is spent searching for limited information. Finally, there are substantial ethical boundaries that must be considered when developing a research plan. This article will discuss the various ethical rules that are implicated in conducting online juror research along with an outline of some research best practices.

ETHICAL BOUNDARIES

In addressing the ethical implication of online juror research, most state bars and courts have stated that the practice falls under Model Rule of Professional Conduct (MRPC) 1.1, which states, “Competence requires the legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation.” (emphasis added).[7] Because an attorney owes a duty of thoroughly preparing a case for a client, he must use all of the resources available, including online juror research. Georgia Rule of Professional Conduct (GRPC) 3.5 provides an outer boundary for this research by stating that a lawyer shall not attempt to influence and/or communicate ex parte with a juror or prospective juror unless authorized by law or court order. Thus, an attorney is authorized to perform online research, but must not do so in a way that communicates with a prospective juror or otherwise may unduly influence a prospective juror.[8]

What Constitutes Communication?

Georgia has not directly addressed the definition of a communication. However, any attempt to view the prospective juror’s private page that requires authorization (such as a friend request) is likely to be viewed as an inappropriate “direct” communication under GRPC 3.5.[9]

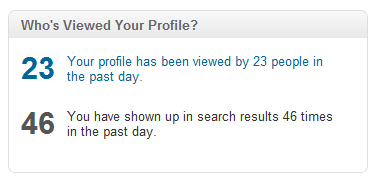

In interpreting the “indirect” communication portion of rule, some state bars have stated that a communication has occurred if a social media website automatically notifies a juror when another person has viewed the juror’s profile page.[10] LinkedIn, for example, will notify a user regarding who has viewed the user’s profile:

Viewing a prospective juror’s LinkedIn account may be considered a “communication” under GRPC 3.5

To avoid this communication, it is important that the attorney always log out of a personal account prior to conducting juror research.

Privacy Concerns

Regarding privacy expectations in a criminal context, “The act of posting information on a social networking site, without the poster limiting access to that information makes whatever is posted available to the world at large.”[11] Along different lines, when concerning a prospective juror, courts have enforced more stringent protections for jurors out of fear that jurors will be less likely to serve on a jury if doing so will subject their personal life to intense scrutiny.[12] Thus, attorneys and investigators should be mindful of potential privacy concerns a juror may have and respect logical boundaries.

SEARCH METHODS

The first step in performing juror research is obtaining a list of potential jurors. As far back as 1709, complete lists of jurors were required to be provided to indicted parties.[13] Prior to the Internet, it was common for investigators to conduct a “drive by” survey of potential jurors’ houses to evaluate whether the juror had children’s toys in the yard, owned a newer vehicle, and the general upkeep of the home and yard.[14] Today, most Georgia courts publicly provide juror lists either through the clerk’s office or by publishing the list in a local newspaper. To help facilitate receiving the list of prospective jurors in a timely fashion, counsel should consider jointly asking the court to enter an order allowing the parties access to the juror pool information regarding the panel members’ names, addresses, and dates of birth.[15] In support of such a motion, counsel may point out that some states, such as Florida, have concluded that an attorney has a right to perform a background check on potential jurors whenever possible.[16]

“Where possible, trial judges should allow counsel to check [public] records, if such a request is made, and it can be done without unwarranted delay. Certainly a small delay at the beginning of a trial would be better than having to do a retrial of a case after it has been concluded.”[17]

Once a juror list has been obtained, an attorney can begin researching prospective jurors online. Prior to a discussion of the nuts and bolts of performing online research, it is important to understand a couple of general points. First, online research is often tantamount to finding a needle in a haystack. There will be many false positives and most accurate search results will yield little, if any, helpful information. However, one piece of information could be the difference between winning and losing at trial.[18] Attorneys can avoid wasting time on false positives by adding geographic filters to a search, such as the city and state whenever possible.

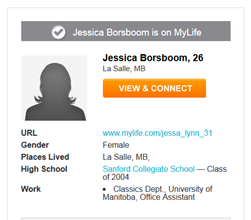

Second, a primary goal in juror research should be to find usernames of jurors. A Google search of “Jane Doe” may yield some helpful results, but “Jdoe31” will almost always reveal more. As discussed below, many social media websites link the username and real name together. These site are particularly helpful for locating unique usernames. Attorneys can also use a data aggregation website like MyLife.com, which automatically links full names and usernames without any input from a user.

Search for a person on MyLife.com and look for a URL name that is something other than numbers. Then, perform a search using that username to identify other resources:

Search Engines

Google.com, Yahoo.com, and/or Bing.com[19] will be the primary vehicles for conducting basic searches for a potential juror’s name and/or username. The only point here is to understand that most search engines use Boolean logic to determine what results to display. “John Doe,” “Doe, John,” and John Doe (without quotation), will each reveal unique results that may not be shared among them. Similarly, use the plus (+) or minus (-) symbols to include or exclude certain terms, such as +Bainbridge or –Kansas.

In addition to the big three search engines, ZoomInfo.com will also provide additional results for working professionals.

Social Networking Websites

Facebook.com

Facebook.com is the largest social media website on the internet. Recent statistics indicate that a majority of United States citizens have a Facebook account and more than 70% of internet users maintain a Facebook account.[20] Despite its large user base, less than one-third of all Facebook users do not utilize some form of privacy protection for their profile. This means that most of the results found during juror research will be inaccessible. Nonetheless, even when a user has his account on complete lockdown, it is still possible to obtain the username for the person by viewing the blocked profile page. Facebook refers to its usernames as “vanity names.” The vanity username appears in the address bar and will look like: http://www.Facebook.com/myusername. You can use this username to find other profiles that may not have the same privacy settings.

Myspace

MySpace.com’s user base has dwindled from tens of millions of users to less than a million over the last five years.[21] This is good news for the savvy internet researcher. User accounts on MySpace generally do not disappear once a user has stopped logging in. Most Myspace accounts have little or no privacy activated. Photo albums, “lifestyle surveys,” and more are easily accessible using the main search box on the homepage and then narrowing down based on geography. Myspace.com should be searched independently, because search engines do not index all of the profile pages on Myspace.

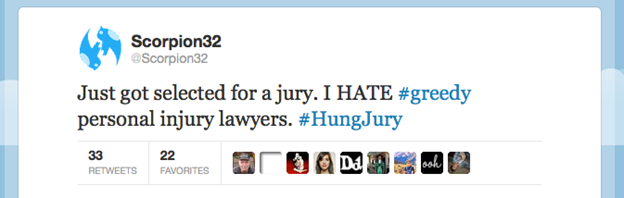

Twitter.com is the fastest growing social media website. Twitter users “microblog” 400 million “tweets” each day. Most Twitter users do not use high privacy settings because the website is designed to encourage communication between strangers. However, searching on Twitter can be difficult for a couple of reasons. First, most user do not use their real names. Second, it requires clicking through multiple pages to reach a page that is searchable by name.[22] If you have already found a username from the methods discussed above, finding an associated twitter account is relatively easy as all usernames are indexed by, and easily searchable through, Google.

LinkedIn.com is primarily used by professionals. The vast majority of information you can find on LinkedIn will also be found on a person’s corporate biography page found through Google. However, the “Groups” a user subscribes to may provide helpful information in focusing your research:

Pinterest.com is a relatively new and rapidly growing social media website that allows users to “pin” articles, photos, and links that they find interesting. Like Twitter, Pinterest has few privacy settings and most users do not activate them. Many Pinterest accounts are not indexed by Google, so it will be necessary to create an account with Pinterest if you choose to include it in your research.

Background Search Resources

Lexis and Westlaw

Lexis and Westlaw each offer a pay service that offers background research on prospective jurors. Both of these services provide basic information on address history, criminal records, household members, civil lawsuits, and other public records. Most Lexis/Westlaw account representatives will offer a free tutorial on accessing and using these resources.

Georgia Department of Corrections

The Georgia Department of Corrections offers a website that allows searching past and present incarceration records. If a result is found, the website will display comprehensive information about the conviction and will even have prior mugshots available. You can search the website at: http://www.dcor.state.ga.us/GDC/OffenderQuery/jsp/OffQryForm.jsp?

Spokeo

Spokeo.com is a data mining company that tracks a variety of social media websites, including Facebook, MySpace, YouTube, and Twitter. Spokeo will also list property records associated with the user and information about other people who live in the same household. Simply type in a name or email address and perform a fairly deep search of social media. A basic subscription to Spokeo starts at $24 for six months.

TLO

TLO.com was created as a “next generation” version of Intelius. TLO reports all of the information contained in the above reports, but also adds in social media accounts, email addresses, and vehicle registrations. TLO institutes a comprehensive background check before access is granted to its databases, which can take several weeks. Thus, an attorney interested in using this resource should apply well in advance.

CONCLUSION

Admittedly, the vast majority of information gleaned from these websites will be unhelpful. However, any helpful information can be invaluable and the success rate of these searches will only increase as social media usage continues to grow. Used properly, online juror research can level the playing field with wealthy defendants, help shorten the voir dire process, enhance juror impartiality, and ultimately promote civil justice for all plaintiffs.

[1] Matt Wetherington is an attorney at the Wetherington Law Firm. Matt graduated from the Mercer University School of Law, and has served on an associate attorney on complex litigation claims throughout the South. Matt is also the founder of the Tire Safety Group.

[2] Pew Internet & American Life Project, Social Networking Report (full detail), available at http://www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/March/Pew-Internet-Social-Networking-full-detail.aspx (last accessed June 1, 2013).

[3] See NYCBA Comm. On Ethics Formal Opinion 2012-2.

[4] Id.

[5] Johnson v. McCullough, 306 S.W.3d 551 (Mo. 2010) (holding that attorneys had a duty to investigate prior litigation history of jurors during juror selection or early in trial); Roberts v. Tejada, 814 So.2d 334 (Fla. 2002); Carino v. Muenzen, A-5491-08T1, 2010 WL 3448071 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Aug. 30, 2010).

[6] State v. Burnette, 2006 WI App 20, 289 Wis. 2d 219, 709 N.W.2d 112 (2006)

[7] This rule is identical to Georgia Rule of Professional Conduct 1.1.

[8] See Also Philadelphia Bar Ass’n Prof’l Guidance Comm. Op. 209-02 (March 2009).

[9] Comment six states, “Direct or indirect communication with a juror during the trial is clearly prohibited.” See Also People v. Fernino, 851 N.Y.S.2d 339 (N.Y. 2008) (holding Facebook friend request constitutes inappropriate contact).

[10] Robert B. Gibson & Jesse D. Capell, Researching Jurors on the Internet – Ethical Implication NYSBA Journal (November/December 2012).

[11] Independent Newspapers, Inc. v. Brodie, 966 A.2d 432 (Md. 2009); Guest v. Leis, 255 F.3d 325, 332 (6th Cir. 2001) (users of social networking sites “logically lack a legitimate expectation of privacy in the materials intended for publication or public posting.”); United States v. Charbonneau, 979 F. Supp. 1177, 1184-85 (S.D. Ohio 1997) (finding no expectation of privacy in chat room discussions); Commonwealth v. Proetto, 771 A.2d 823, 831 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2001) (finding no expectation of privacy for personal website); United States v. Maxwell, 45 M.J. 406, 417-19 (C.A.A.F. 1996).

[12] Thaddeus Hoffmeister, Investigating Jurors in the Digital Age: One Click at a Time, 60 U. Kan. L. Rev. 612 (2012).

[13] Id. (quoting the English Treason Act of 1708).

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Roberts ex rel. Estate of Roberts v. Tejada, 814 So. 2d 334, 337 (Fla. 2002)

[17] Id.

[18] For a great survey of “war stories” involving online juror research, Stephen Laitinen & Hilary Loynes, A New “Must Use” Tool in Litigation?, For the Defense (August 2010).

[19] All three search engines can be combined on a variety of websites, including www.DogPile.com

[20] Jackie Cohen, 71 Percent Of U.S. Web Users Are On Facebook, available at http://www.allfacebook.com/71-percent-of-u-s-web-users-are-on-facebook_b27968 (last accessed June 5, 2013).

[21] Alexis Madrigal & Nicholas Jackson, The Rise and Fall of MySpace, The Atlantic (Jan 12, 2011).

[22] https://twitter.com/search/users?q=YourSearchHere