PROTECTIVE ORDERS: KNOWLEDGE IS POWER

Posted by Wetherington Law Firm | Articles

- Articles

- Artificial Intelligence

- Car Accidents

- Class Action Lawsuit

- Comparative Negligence

- Crime Victim

- Defective Vehicles

- Disability

- Kratom Death and Injury

- Legal Marketing

- Motor Vehicle Accidents

- News/Media

- Other

- Pedestrian Accidents

- Personal Injury

- Results

- Sexual Assault

- Truck Accidents

- Uber

- Wrongful Death

Categories

Practice Tips: Best Practices for Protective Orders in Georgia Courts

By Matt Wetherington & Ben Levy

Secrecy is a tactic used by corporations to deprive individuals of the ability to make informed decisions and participate in public discourse about their safety, health, and financial interests. The primary secrecy tools used by corporations are protective orders and confidential settlement agreements. A protective order is a legally binding document that prevents a victim and his or her attorney from obtaining certain information from a corporation, using information obtained in the case to help other victims, or exposing the corporation’s practices to the public. “[P]rotective orders impair the public’s access to discovery records as well as the parties’ First Amendment right to disseminate information to the public.” Westinghouse Elec. Corp. v. Newman & Holtzinger, 46 Cal.Rptr.2d 151 (Cal. App. 2d Dist. 1995). See also, Does I through III v. Roman Catholic Church of Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Inc., 122 N.M. 307, 314-315, 924 P.2d 273. Protective orders should therefore be narrowly drawn, since they implicate constitutional rights of free speech and access to the courts. Seattle Times Co. v. Rhinehart, 467 U.S. 20, 34-37 (1984) (subjecting protective order to First Amendment scrutiny).[1] This paper is written to help reign in protective order abuses and ensure a fair playing field for victims of corporate negligence and malfeasance.

Timing Matters

In most cases, a defendant will improperly respond to a routine discovery requests by stating that … at some point in the future … they will produce some documents of their choosing … after the entry of a protective order. Here is a recent example:

This kind of response is improper for several reasons. Most notable here is the defendant’s effort to delay discovery by not seeking a protective order until serving its discovery responses. As Judge Wayne M. Purdom has written, “[t]he timing of the motion for a protective order is important. The motion must be filed before the due date for the discovery or the date that the deposition is to be taken, and not afterwards.” Ga. Civil Discovery § 4:8 (citing Millholland v. Oglesby, 115 Ga. App. 715, 155 S.E.2d 469 (1973). Similar rules apply in Federal Court. Interested Underwriters at Lloyd’s v. M/T San Sebastian, 508 F. Supp. 2d 1243, 1248 (N.D. Ga. 2007). A defendant’s failure to timely file a motion for protective order can result in outright denial of a motion for protective order.

The Defendant Bears the Burden of Proving Need

Even when defendants timely file their motions for protective order, they often use a ploy that shifts the burden of proving the need for a protective order to the plaintiff. Do not fall for this trick. The defendant must “clearly demonstrate” the need for a protective order. Young v. Jones, 149 Ga. App. 819, 824, 256 S.E.2d 58 (1979); accord Apple Inv. Properties, Inc. v. Watts, 220 Ga. App. 226, 228, 469 S.E.2d 356 (1996); Purdom, Ga. Civil Discovery § 4:8; Ga. Unif. Super. Ct. R. 6.1. The entry of a protective order is proper only if the movant satisfies a two-prong test. First, a motion for protective order must state facts that are clearly demonstrated rather than conclusory statements. Young, 149 Ga. App. At 824. Second, there must be a showing of a need to protect a party from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense. Alexander Props.Group v. Doe, 280 Ga. 306, 626 S.E.2d 497 (2006). Blanket assertions of privilege do not satisfy this burden and are disfavored as a matter of law. See Johnson v. Treasury Dept. 917 F. Supp. 813, 821 (N.D. Ga. 1995); See also United States v. Finley, 917 F.Supp 813, 597 (5th Cir. 1970) (“utilization of a blanket assertion of privilege…is unacceptable and improper…and a claim to the contrary borders on the cavalier”). Practically speaking, this is a higher burden than most defendants recognize.

In state court, a protective order is intended to prevent a “trade secret or other confidential research, development, or commercial information” from being disclosed or ensure that it be disclosed only in a designated manner. O.C.G.A. § 9-11-26(c)(7). Georgia law defines a “trade secret” as information that “is not commonly known,” “[d]erives economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known,” and “[i]s the subject of efforts that are reasonable under the circumstances to maintain its secrecy.” O.C.G.A. § 10-1-761(4); see Purdom, Ga. Civil Discovery § 5:4 (applying Trade Secrets Act to scope of civil discovery).

In federal court, Fed.R.Civ.P. 26(c)(1)(G) governs the protection of “trade secret or other confidential research, development, or commercial information.” A defendant meets its burden by proving “(1) they consistently treated the information as a closely guarded secret, (2) the information represents a substantial value to the Defendants such that it would be valuable to the Defendants’ competitors, (3) the information derives its value by virtue of the effort of its creation and lack of dissemination.” Chicago Tribune Company v. Bridgestone/Firestone, Inc., 263 F.3d 1304 (11th Cir 2001).

In both courts, the proper way to meet the burden is through affidavits and specific statements about what the defendant seeks to protect. Once specific allegations are asserted, diligent counsel will compare the documents at issue to existing case law. Trade secrets are highly sensitive pieces of commercial information like the recipe that an asphalt manufacturer uses to produce its product. Douglas Asphalt Co. v. E.R. Snell Contractor, Inc., 282 Ga. App. 546, 549-50 (2006). Trade secrets are not routine documents that will embarrass or annoy the defendant if produced in open court.

Several proprietary processes and documents are not actually protected under Georgia or federal law. For example, where a purportedly confidential process can be gleaned from observing it—like an automotive parts vendor’s process of taking unordered parts on regular sales runs in the hopes of selling those parts—that process is not a trade secret. Allen v. Hub Cap Heaven, 225 Ga. App. 533, 535 (1997); see also Leo Publications, Inc. v. Reid, 265 Ga. 561, 563 (1995). Even a highly complicated algorithm for buying and selling property, which included a “compilation of property-specific information, its national database on tax redemption behavior, and its final bid guidelines for tax deeds sold at auction” was considered not a trade secret. Capital Asset Research Corp. v. Finnegan, 160 F.3d 683, 686-87 (11th Cir. 1998). Finally, just because employees are forced to sign confidentiality agreements does not mean the process is automatically a trade secret. Equifax Servs., Inc. v. Examination Mgmt. Servs., 216 Ga. App. 354, 39-40 (1994). Effective plaintiffs’ attorneys force defendants to check the boxes.

Negotiate a Fair Protective Order

Irrespective of the need for a good cause showing, attorneys often stipulate to protective orders for a variety of reasons. In this regard, the following issues should be considered when contemplating or negotiating a protective order:

Define “Confidential”

Most protective orders proposed by defendants contain an overly expansive definition of “confidential.” Here is a particularly bad example:

Here is a better definition that complies with state and federal guidelines for protective orders:[2]

The burden of proving that any corporate policies and, particularly material reflecting or related to policies and procedures, previous claims, and previous lawsuits contains confidential information is on Defendant. Prior to designating any material as “CONFIDENTIAL,” the designating party must make a bona fide determination that the material is, in fact, a trade secret or contains other confidential information, the dissemination of which would damage the designating party’s competitive position. If the designating party has a good faith factual and legal basis for asserting a privilege or exemption from public disclosure, the designating party may designate as “CONFIDENTIAL” the portion of any produced material it considers subject to its claim of privilege or exemption.

When defining confidential material, consider whether it should be limited solely to a particular document, category of documents, or documents responsive to a particular discovery request.

Streamline the Challenge Process

The protective order should provide a clear procedure for challenging improper confidentiality designations. Here, defendants will often attempt to shift the burden onto the plaintiff to petition the court and prove that the documents are improperly designated. This is the opposite of how it should work. Here is an example of a challenge provision that properly keeps the burden on the defendant:

By entering into this Order and agreeing to its terms, Plaintiffs do not concede that documents or information designated by Defendant as “CONFIDENTIAL” do in fact contain or reflect confidential information, and Plaintiffs reserve the right to challenge any such designation. Further, Plaintiffs shall not be obligated to challenge the propriety of the designation of information as “CONFIDENTIAL” at the time made, and failure to do so shall not preclude a subsequent challenge thereof whether during the pendency of this litigation or afterwards. If, during the pendency of this litigation, any party wishes to object to any such designations, the following procedures shall apply:

- Plaintiffs shall notify counsel for Defendant in writing of such objection. Defendant shall then have ten (10) days thereafter to respond in writing either withdrawing the “CONFIDENTIAL” designation or otherwise resolving the objection.

- If the objection cannot expeditiously and informally be resolved, Defendant must file a motion seeking a ruling from the Court within fourteen (14) days of receiving Plaintiffs’ objection.

The designated information at issue shall continue to be treated as “CONFIDENTIAL MATERIAL” as designated until the Court orders otherwise.

This procedure ensures that the process is fair for the plaintiff and complies with the generally accepted procedures for maintaining confidential status of documents. See, e.g., McCarthy v. Barnett Bank of Polk County, 876 F.2d 89, 90 (11th Cir. 1989) (approving protective order that “allows the producing party to designate a document confidential unless the other party objects,” and in the event of an objection, allows the producing party to move the court for a ruling or concede the objection); In re Alexander Grant & Co. Litig., 820 F.2d 352, 354 (11th Cir. 1987) (approving protective order that provides that once a notice of objection to a confidentiality designation was received, the producing party had ten days to apply to the district court for a ruling to keep the material confidential). Also, be wary of any provision that tries to limit the use of a document if a court denies a motion to file under seal, as is used in federal courts.

Sharing Provisions Promote Justice

Today, a parent can purchase a product unaware that a defect in its design has killed dozens of children and been the focus of litigation across the country. When that product eventually kills or injures another child, his or her parents are unlikely to learn of other victims or discover that the manufacturer knew of the defect for years and took no action to warn the public. If the parent files a lawsuit against the manufacturer, their attorney will not benefit from the progress made by other families. Instead, the manufacturer will hide the existence of other injuries and force the parent to duplicate all of the investigative work performed by other claimants. The manufacturer benefits greatly from this approach because most cases do not justify expensive, multi-year litigation against a corporation. Most parents abandon their claims, settle for pennies on the dollar, or have their case dismissed due to an inability to obtain documents necessary to support their case. Sharing puts an end to this process.

Sharing supports the goals of the Civil Practice Act for several reasons. First, it levels the playing field between corporate wrongdoers and their victims. Collaboration also enables better, more prepared advocacy and further narrowing of the issues for trial. Second, sharing reduces costs. Discovery is an expensive, laborious process, and it only becomes more so if it must be repeated from beginning to end in every case. Third, and perhaps most importantly, sharing enables requesting parties to ensure that the producing party has complied with its obligations and has not withheld categories of documents. It is a plaintiff’s only way to determine whether a large corporate defendant has complied with its discovery obligations or has withheld categories of documents. As explained by one United States District Court:

In this era of ever-expanding litigation expense, any means of minimizing discovery costs improves the accessibility and economy of justice. If, as asserted, a single design defect is the cause of hundreds of injuries, then the evidentiary facts to prove it must be identical, or nearly so, in all cases. Each plaintiff should not have to undertake to discover anew the basic evidence that other plaintiffs have uncovered. To so require would be tantamount to holding that each litigant who wishes to ride a taxi to court must undertake the expense of inventing the wheel.

Ward v. Ford Motor Company, 93 F.R.D. 579, 580 (D. Colo. 1982).

Moreover, the Supreme Court of Texas has observed:

The “rules of the game” encourage parties to hinder opponents by forcing them to utilize repetitive and expensive methods to find out the facts … The truth about relevant matters is often kept submerged beneath the surface of glossy denials and formal challenges to requests until an opponent unknowingly utters some magic phrase to cause the facts to rise…Shared discovery is an affirmative means to insure full and fair disclosure. Parties subject to a number of suits concerning the same subject matter are forced to be consistent in their responses by the knowledge that their opponents can compare these responses.

Garcia v. Peeples, 734 S.W. 2d 343, 347 (Tex. 1987).

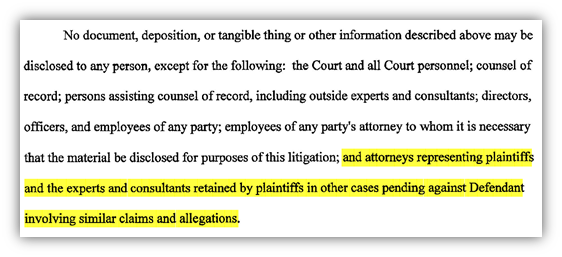

Here is an example of a sharing provision from a recent case:

In summation, a sharing provision is an important safeguard in any protective order and is worth fighting for.[3]

Conclusion

There are many forms of protective orders, and what makes sense in one case may not make sense in another. However, secrecy is rarely good for a lawyer, his client, or the civil justice system.

[1] See Highfield, V. The Kroger Co., 2014 WL 10742498 (N.D.Ga.) for excellent briefing on the public policy issues highlighted by protective orders.

[2] The purpose of this article is not to provide a form document to follow blindly, but to provide broad examples for consideration in revising or proposing a protective order under the facts of your unique case.

[3] See also Cipollone v. Liggett Group, Inc., 113 F.R.D. 86, 87 (D.N.J. 1986) (“[R]equiring each plaintiff in every similar action to run the same gauntlet over and over again serves no useful purpose other than to create barriers and discourage litigation against the defendants. Good cause as contemplated under Rule 26 was never intended to make other litigation more difficult, costly and less efficient.”); Ward v. Ford Motor Co., 93 F.R.D. 579, 580 (D. Colo. 1982) (allowing sharing of documents to reduce “effort and expense inflicted on all parties…by repetitive and unnecessary discovery. In this era of ever expanding litigation expense, any means of minimizing discovery costs improves the accessibility and economy of justice…Each plaintiff should not have to undertake to discover anew the basic evidence that other plaintiffs have uncovered. To so require would be tantamount to holding that each litigant who wishes to ride a taxi to court must undertake the expense of inventing the wheel. Efficient administration of justice requires that courts encourage, not hamstring, information exchanges”); Burlington City Bd. of Educ. v. U.S. Mileral Prod. Co., Inc., 115 F.R.D. 188, 190 (M.D.N.C. 1987) (“Permitting plaintiffs to share information helps counterbalance the effect uneven financial resources between parties might otherwise have on the discovery process, thereby protecting economically modest plaintiffs faced with financially well off defendants and improving accessibility to justice.”); Kamp Implement Co., Inc. v. J.I. Case Co., 630 F. Supp. 218, 219 (D. Mont. 1986) (Collecting cases and recognizing, “[o]f the courts that have considered protective orders of the nature proposed by defendant, an overwhelming majority have refused to grant any type of protection from dissemination.”); Wolhar v. General Motors Corp., 712 A.2d 464, 467 (Del. 1997) (“The great weight of authority in other jurisdictions holds that such sharing is not only theoretically sound but also justified as an efficient use of the resources of the courts and the parties.”); Burlington City Bd. of Educ. 115 F.R.D. at 190 (Collecting cases and noting, “the sharing of information between even diverse plaintiffs promotes speedy, efficient and inexpensive litigation by facilitating the dissemination of discovery material necessary to analyze one’s case and prepare for trial.”).